I was once given a programming exercise to complete for a job I was applying for. The exercise seemed pretty simple. Given a set of specs, make the code work. The specs were in rspec, which happens to be my testing tool of choice. I thought it should be pretty straight forward.

Turns out the specs made heavy use of contexts. So many, in fact, that I could barely figure out what the tests were testing. I was constantly jumping around the file, trying to figure out what context I was in.

I didn’t get the job.

Fast forward several years and now I like contexts. I finally get it. And I think I know why. This will either try to explain how well written contexts work, or convince you to give them a shot if they have seemed frustrating to you in the past.

RSpec Code Without Contexts

Before I dive in, it makes sense to set some sort of baseline of what a context is. In rspec, tests are written in the form of describe and it blocks.

The describe block sets the basis of the test, and the it block sets up specific use cases. If we were to test a car class that takes a number of doors as a parameter, it might look like this.

describe Car do

describe "#initialize"

let(:car) { Car.new(2) }

it "has a set of of doors" do

expect(car.doors). to eql 2

end

end

end

That’s simple enough. Declare the class we are working with (Car), describe the method under test (initialize), set up the object under test (let), and then declare some use cases. In this case, test that the car has the same number of doors we declared when we created it.

RSpec Code with Contexts

These types of specs are fine. And I prefer them in many situations. If I were just writing some simple tests, I might just fill an entire file with specs just like this.

But sometimes the test might test the same method in different contexts. Authentication is a good example.

The flow might be when authenticated, do this. When unauthenticated, do this.

RSpec.feature "Admin Add Users To Vendor", type: :feature do

context "without authentication" do

scenario "denies access to non-admins" do

visit "/admin/vendors/1"

expect(current_path).to eql admin_sign_in_path

end

end

context "with authentication" do

let!(:vendor) { FactoryBot.create(:vendor) }

let(:user) { FactoryBot.create(:user) }

before do

sign_in_as_admin

visit "/admin/vendors/#{vendor.id}"

end

scenario "and a valid user adds user to vendor" do

fill_in "email", with: user.email

click_on "Add User"

expect(page).to have_content user.full_name

end

end

end

This example is a little different, but it’s same concept. This is a feature spec in rspec, but almost everything in rspec is syntactic sugar on top on describe and it blocks. In fact the first line that has Rspec.feature is an alias for describe. Don’t get too hung up on the specific words used. Concentrate on the form.

You can see how the contexts break and it up and start to make sense. The “without authentication” context asserts that any non-authenticated user is redirected properly. This could contain more use cases as the codebase grows in complexity.

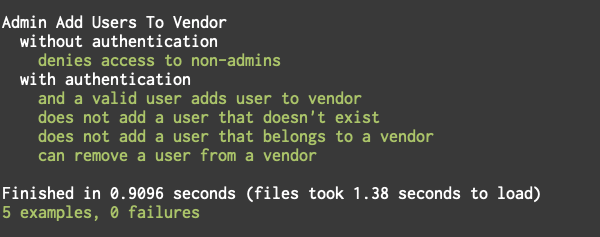

You can also start to see how you should name your specs. The grouping really helps. When I’m looking at a spec, I often run this type of documentation so I can see how it should work.

rspec -f d [path to file]

If I knew nothing about the codebase before running this spec with the documentation formatter, this would tell me enough to what it’s responsibilities are.

Where to Use Contexts

I think specs with contexts and specs without contexts both have their place. If your specs are pretty simple, then contexts add overhead, but not much value. On the other hand, if your code reacts differently to certain inputs, contexts can really help with readability. And readability is really the only reason to use them.

I mentioned using contexts if your code reacts differently to certain inputs.

A good way to determine if contexts would help, other than just seeing that your spec file is confusing, it to use cyclomatic complexity.

I would say any score higher than three would be a good case for contexts. Or in other words, if you have have at least three paths through a chunk of code, I would consider breaking that up into contexts.

If your test code is hard to read or understand, or the complexity of the code your testing calls for different contexts, give rspec contexts a shot and see if it helps.